Article

‘Undefining’ Architecture…

As an architect who has worked in the industry for over 30 years, the pandemic gave me enough time to reflect on an answer that I have been searching for and then another two years to pen this down. What constitutes ‘successful’ Architecture? Over the decades, I have pondered over this question but never really delving deep enough to arrive at an answer. I suppose I kept redefining it, to fit within prevailing theories and movements.

As a student, I was inspired by the grandness of scale, exciting forms and dynamism of the spaces - The sharply delineated, utilitarian designs of the Modernist Movement, the sculptural forms of Zaha Hadid and the stark integrity of Tadao Ando’s Architectural translations.

As the years progressed, I felt it was too facile an answer. Architecture was not only that, but it was also a response to a context, a site. Architecture could be loosely defined as the art of building, but it was really about the efficient creation of spaces that also stimulate the mind. Perhaps through their quality, the interplay of light, the incorporation of Nature, the comfort of the user.

A decade into the field and the above thoughts further evolved to include quantifiable sustainability. Terms like low embodied energy, carbon footprint, zero discharge projects, building performance indices, were learnt, emphasized and propagated. Architecture became a series of building envelope calculations and a successful building was one that achieved the desired rating. The answers seemed to lie in restoring the resources the industry had pillaged in the past.

Of course, after having worked in the industry and designed several projects, one does realize that architecture must encompass all of the above: A response to the site, well juxtaposed forms, articulated spaces, climate sensitive and carbon negative footprints.

However, as I teach Architecture today, reverting to academics and theorizing design, I feel that Architecture can only be termed as successful if it involves a degree of social engineering. The days of an architect being perceived as a ‘solitary genius’ are long past. The architect must be part of a participatory process, involved in uplifting the community and galvanizing it towards a better future. The architect must strive to create an architecture that is unfettered and extends beyond its realms- touch lives, meet a need, exist beyond its boundaries.

With this article I would like to highlight three such simple structures that brought about a far reaching social impact as well as ecological justice.

The Warka Towers:

The name ‘Warka’ comes from the Warka Tree, which is a giant, wild fig tree native to Ethiopia. Like the tree, the Warka Tower serves as an important cornerstone for the local community, becoming part of the local culture and ecosystem by providing its fruits, shade and a gathering place. The design was conceptualized by Arturo Vittori and has been operational in Ethopia since 2015. The idea was conceived as a solution for isolated villages situated on the North Eastern plateau regions where Villagers lived in environments often without running water, electricity, a toilet or a shower. Vittori observed how women and children had to walk miles to shallow, unprotected ponds where water was often contaminated with animal and human waste. In almost every rural household, women and girl children bear the responsibility of collecting, transporting, storing, providing and managing water. The average distance that women and children walk daily for water in Africa is six kilometers. Furthermore, they carry about 20 liters of water on their heads severely damaging their neck and spine over time. Conservative estimates indicate that people in sub Saharan Africa spend up to 40 billion hours a year fetching water.

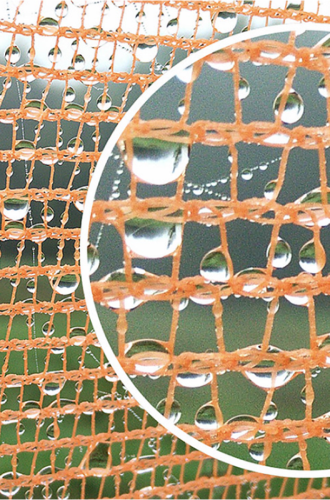

The design of the towers aims to provide this basic human need through the principle of condensation. The warmer the air and the higher the relative humidity in it, the more water vapour it can produce. The simplest way of drawing water from air is using passive technology that provides a cool surface for water vapour to condense onto. These 30-foot vase shaped towers can extract up to 100 litres/day without using fuels, chemicals or power. This water is collected between dawn and dusk and is stored in chambers below the surface of the earth.

Since these towers are easy and inexpensive to construct, they can be replicated across the region by villagers themselves using local materials. Just by providing access to the basic need of clean water the following lifestyle improvements have taken place:

· Women have more time to care for their children and family.

· Given girl children the opportunity to go to school.

· Decreased infant mortality.

· Empowered the local economy by creating better crops

· Preserved local community culture.

The Warka Towers

The Warka Towers

The Warka Towers

The Warka Towers

Floating Schools, Bangladesh:

To ensure that waterlogging during frequent flooding does not restrict the education in the low-lying regions of Bangladesh, Architect Rezwan, founder of a non-profit organisation called Shidhulai Sawanirvar Sangstha designed floating schools that help impart education in the rural communities. To confront the uncertainty of the weather, Rezwan designed self-reliant solar-powered boats which include a small library, space for laptops, batteries and solar lamps.

The material used for building is usually bamboo that was weaved to make the roof and side barriers to protect them from the monsoon.

By this simple structure Shidhulai physically created a supplement to the lost amenities on the land but succeeded in changing lives- he not only gave hope but succeeded in inspiring a society to dream. The success of this small non-profit venture percolated into the socio-economics the region by diversifying into floating medical clinics, libraries and even playgrounds on the river.

Floating School, Bangladesh

Floating School, Bangladesh

Floating School, Bangladesh

Floating School, Bangladesh

Ice Stupas of Ladakh:

This much publicized innovation, the brainchild of Sonam Wangchuk is a step towards a sustainable solution to solve the water woes of the region of Ladakh.

The Land is a cold arid desert surrounded by spectacular lofty mountains against azure cloudless skies. The climate is harsh and extreme. Winter temperatures often dip below -30 degrees Celsius and the area receives less than 50mm of annual rainfall. Ladakhi communities depend on farming for their livelihood relying largely on melting glacial water for their crops. This dependence on the glacier is so strong that local folklore often revolves round stories about them.

Unfortunately, in recent years, the snowline has been shifting due to global warming. “We can see that glaciers are receding, and they’ve gone higher and higher,” says Wangchuk. Glacial streams are beginning to dry out before the summer even starts, creating water shortages during the spring when newly planted crops are vulnerable.

Wangchuk devised these ‘ice stupas’ as he called them, to resolve the shortage of water, based on the key principles of gravity and the fact that water stays at a uniform level. They are formed by running pipes below the frost line where the temperature of the water hovers between a liquid and solid state. Then the pipes turn skywards, spraying the water into an ambient air temperature of -20C, using the bitter cold to freeze it as it falls to the earth. This allows the water to freeze in a conical form resembling ‘Stupas’ which can be stored and used in the spring when it melts for planting crops and drinking. Each stupa has a capacity to store at least 30-50 lakh litres of water.

This simple solution has brought about a complete change in the lifestyles of the Ladakhis and several villages which had been abandoned due to the shortage of water were re-inhabited.

Families that were forced to leave their traditional agrarian practices and work as daily wagers or run utility shops to make ends meet, had turned several villages into ghost towns and wasted agricultural land. With the combined efforts of the people, NGO’s and the government these villages began to flourish again, rejuvenating the community and their spirit.

Ice Stupas of Ladakh

Ice Stupas of Ladakh

Ice Stupas of Ladakh

Ice Stupas of Ladakh

To me, these above examples are what I would term as true architecture living up to all its possible definitions and integral to its essence in every way. As architects, we must want to create architecture outside the confines of our prescribed roles- impacting the quality of life through involvement beyond our purview. As citizens of society, we can influence social conditions and can even be the cause of positive social change. This is what I believe is the final factor to determine the success of a structure. Architectural History has recorded several monuments, magnificent edifices of grandeur and technological marvels. How many though can claim to have touched the lives of the distressed in a way that brought back a smile that shines through their tears.

This is what I would term beyond Architecture…

Bibliography

https://www.warkawater.org/

https://indianexpress.com/article/india/ice-stupas-help-ghost-villages-of-ladakh-become-habitable-again-6554438/

https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/this-floating-school-is-changing-lives-for-kids-li/

https://ideas.ted.com/no-theyre-not-a-mirage-learn-how-these-ingenious-ice-towers-are-helping-communities-preserve-water-for-dry-times/

5 Examples of architecture used for social change - RTF | Rethinking The Future (re-thinkingthefuture.com)

Read More

- © 2024 SSA. All Rights Reserved.

- Terms of Use